''Bill is a genius," says Chris Jennings. "The show epitomizes his genius. It's the perfect blend of music, dance and theater -- a completely unique theatrical experience.''

Jennings, managing director of the Shakespeare Theatre Company, is talking about Fela!, the popular Broadway musical co-written, directed and choreographed by Bill T. Jones. The Shakespeare Theatre has brought back the show, about the late, legendary Afrobeat pioneer and Nigerian political activist Fela Kuti, for a short run. Fela! kicks off its second national tour just as it did its first, in 2011, at the company's Sidney Harman Hall, thanks to STC's initiative – Jennings says the show was set to skip Washington both times otherwise.

''I've never seen dance like this within a theater production,'' Jennings adds.

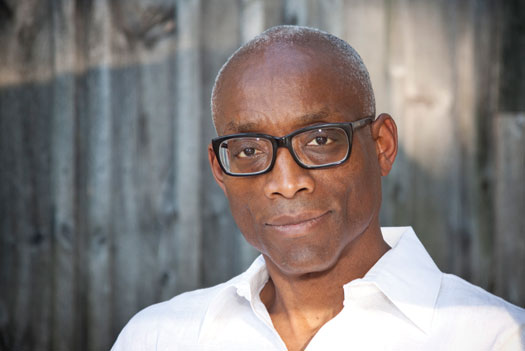

Bill T. Jones

(Photo by Stephanie Berger)

That's definitely not the first time anyone has called Jones's work unique. In fact, his repertoire has been built on a revolutionary spirit. And just as certainly, it won't be the last. Actually, soon enough similar praise is sure to be said about Jones's latest work, A Rite, a hybrid theater/dance piece. The work is a rare collaboration between two performing arts groups, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company and the theater group SITI Company, led by Anne Bogart.

''You have dancers who are acting, and actors who are dancing, and that's pretty amazing,'' says Bogart, about the piece's cross-disciplinary approach. ''I hope it's breaking new boundaries.''

A modern adaptation of the ballet The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky and Vaslav Nijinsky, A Rite premiered last week at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. When the now-classic The Rite of Spring debuted 100 years ago in Paris, it was met with disdain, provoking strong reactions for the avant-garde nature of its music and choreography, and for its pagan story. Commissioned by Carolina Performing Arts and now touring the country, including a stop next week at Maryland's Clarice Smith Center, the new A Rite finds ''two communities coming together, an acting company and a dance company,'' explains Bogart, ''working together and creating one community.'' In an early review, The New York Times dance critic Alastair Macaulay called A Rite ''a serious, intricate, multidirectional centennial tribute to a work of art whose spell it deepens.''

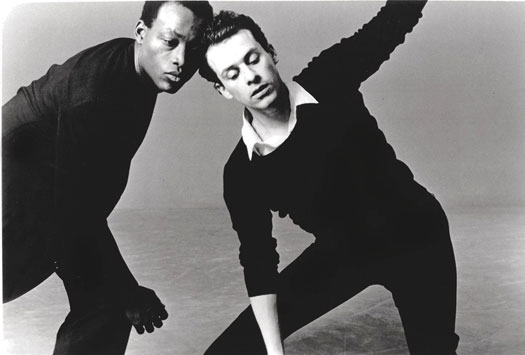

Jones, you could say, has been putting dance lovers under his own spell for over three decades now. He started his dance company with Arnie Zane in 1982, after Jones and Zane had met and fallen in love in college. Jones, who grew up in western New York, was on a track scholarship at Binghamton University. But he quickly shifted gears from running to twisting and leaping, dancing solo and with Zane. After Zane died of AIDS-related lymphoma only six years into their artistic partnership, Jones threw himself into his work. Among other products from his mourning period, Jones created the moving piece Absence in memory of Zane.

In the decades since, Jones has gone on to great acclaim and success – without ever shying away from controversy or being honest and frank about who and what he is. For one thing, Jones has been openly gay from the start of his career. He also hasn't flinched from discussing his life and health as an HIV-positive man.

In fact, if it weren't for the advance of age, the healthy, incredibly fit Jones, who turns 61 the day after Valentine's Day, would surely still be dancing. But older bones rattle a little louder and take longer to mend than those of a younger man. So these days Jones's focus is on choreography, chiefly for his company, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. In 2011, the company teamed up with Manhattan's Dance Theater Workshop to create the performing arts venue New York Live Arts, where Jones is executive artistic director. Jones sees the organization as one way of giving back, as he puts it, to ''the field that made me. New York Live Arts is devoted to cultivating progressive, if you will, avant-garde people: body-based artists at every stage of their career.'' The venue, in Chelsea, is also now the permanent home for Jones's dance company.

Of course Jones has become best known over the past decade for his work on the Great White Way. He's now two for two at the Tony Awards for his choreography: winning in 2007 with Spring Awakening and 2010 with Fela!

Certainly his work on Broadway solidified his selection in 2010 as a recipient of the Kennedy Center Honors, the nation's leading award honoring a lifetime of achievement in the arts.

''The very, very best are not content doing good work, or popular work. They insist on being revolutionaries,'' said playwright Edward Albee, a 1996 Kennedy Center Honoree, in recognizing Jones's work at the Kennedy Center ceremony. Albee continued: ''If you meet Bill T. Jones, what do you see? Well, you see a man of only a little bit more than average height. But then you watch him, Bill T., dance. And you see his amazing choreography. And you begin to realize that Bill T. Jones, indeed, stands taller than most other men.''

For her part, and also at the Honors ceremony, actress Claire Danes, who got her start in New York's theater and dance scene, succinctly summed up Jones's influence: ''Bill T. Jones is, simply, an inspiration.''

In the past couple weeks Jones has been consumed with A Rite, getting it in shipshape and ready to tour. But he took some time out to talk to Metro Weekly by phone from North Carolina, days before the piece's world premiere – and one day after President Obama's second inauguration. The president's incredibly pro-LGBT speech, and how ''it will play'' among Jones's more homophobic African-American brethren, almost beat out A Rite as the topic at the forefront of his mind.

METRO WEEKLY: I understand you are not in your company's new piece A Rite coming to the Clarice Smith Center.

BILL T. JONES: No, I'm not.

MW: You don't dance much these days?

JONES: No, I don't really. I dance when I'm very happy. And in special situations. I danced at our company gala, at the New York Live Arts, a month or so ago. If there's been a beautiful performance and the audience is warm, I might do something impromptu. Or I dance when my companion is making a lovely dinner. Or with friends and a bit drunk.

MW: But not onstage in a performance.

JONES: No, I have not of late made pieces for my body. I would like to do it. I intend to do something. I have to be careful I don't break anything. The ankles and knees and lower back are those of a 61-year-old man. My body is in good shape, but I can't writhe it like my dancers do every day working six or seven hours up on their feet, and stretching and bending and jumping. I don't long to do that. It has to be somehow different. It has to be another ritual of sorts.

MW: When did you last dance onstage?

JONES: Six, maybe seven years ago, a solo I did at the Louvre in Paris, called ''Walking The Line.'' That was my last official public performance.

MW: Since then, you've gone on to greater public recognition, including successful forays on Broadway. But receiving the Kennedy Center Honor in 2010, alongside Oprah Winfrey and Paul McCartney, must take the cake.

JONES: Oh, please, I felt a bit like Mr. Obama at his second inauguration. As he was leaving, he turned around and said, ''I'll never see this again.'' Well, it almost felt that way for me. [Laughs.] You know, being honored, by the president and at the Kennedy Center. I don't expect to have that repeated in this life. You can't get many more honors like that.

Bill T. Jones

(Photo by Christina Lane)

MW: So you took time out of your last-minute preparations of A Rite to watch the inauguration?

JONES: It's funny. I had back-to-back interviews starting at 10 a.m. and going until 1 p.m. A wonderful writer from Chapel Hill called just as the president was taking the oath. I told her that he was about to deliver the inaugural address. I asked her if I could call her back. She said, ''You know, I'm watching it as well.'' So we both took a break and watched it. And really, when she came back on, I was another person. The emotion the address had stirred up really fueled our discussion. But also, it shed a needed light of encouragement on what we are sort of trying to do in our new piece A Rite.

A Rite is almost diametrically opposed in tone to the president's speech, which is all positivity and so on. This piece is very dark. But it did focus what we are pushing against. What we are trying to describe, to say without saying it. Something about the piece that Stravinsky and Roerich made a hundred years ago was very much of its time. The piece that we're trying to make now, using that music – and other music – is very much of our time. Is there a sacrifice in their work? Yes. A sacrifice was made and it's very clear. Is there a sacrifice in our work? Yes. It's not as clear. The excitement has been trying to negotiate this ambiguity in the piece. And of course the two companies, the two cultures, coming together to make it, struggling with this question, of sacrifice and meaning and art and so on. It has been its own reward, but there is that central question: What is our sense of the one and the many? The individual and the collective? I'm talking a lot at you, but these are the things that were brought up by that inaugural address here on the eve of our premiere in North Carolina.

MW: Do you wish you had been on the Mall, or involved in some way with the Inauguration and inaugural festivities?

JONES: Not at all, not at all! [Laughs.] I don't like big groups like that. It felt, appropriately, staged-managed. Everything about it: the flag-waving, the multiculturalism of it, all of those things. All very well and good. It was spectacle. A necessary moment. But what I want to see is, let's get down to business and make things happen. I don't need to be there to rah-rah-rah. The president has my vote, and I have great respect for him and I want him only to succeed. I want him to succeed, not that we need it, but I want him to succeed because he's a black man. And I want to show the world that he can be an exemplary president. I don't need to be there in order to do that. No, I want to be here where I am, right now. Even right now as we're talking, I have – what time is it now? In about half an hour I have to be in the theater, and that's all I can think about today – getting in the theater and cleaning up that second act and getting this thing ready to show.

MW: You're preoccupied, in other words.

JONES: I am, I am. Well, let's say I'm focused. [Laughs.]

MW: I wanted to ask you to reflect a bit on the changes you've seen over the course of your career as a gay man, out from the get-go, even before the AIDS epidemic. It seems a lot has changed in just the past decade, especially.

JONES: Well, you know, yesterday was the first time we've ever heard a president in an inaugural address talk about – make at least two, if not three, references to us as gay people. We were sitting and watching it – I was sitting next to my companion, Bjorn Amelan, and we were watching it, and when he said, ''our gay brothers and sisters,'' I immediately, without even thinking, gave the power salute. My hand shot up with a fist like that, without even thinking about it. And I was so moved that I was almost on the verge of crying. I felt a little ridiculous. We're so thirsty for it. We're still thirsty.

It is now real. When he says that, and everyone around the world heard him say that. And no matter if you're a Christian with your Bible-held beliefs. No matter where you are, left, right or center. It is part of the public dialogue, big time now. We exist. We exist. Hallelujah, we exist. I'm thinking of the people – I live in a little suburban town in New York. And I've been there a long time, and nobody ever addresses it, but I think, they don't have to whisper anymore about me and my companion being together. They know what we are. You don't have to tell them. They know gay people exist. And what's more, we exist for the president – which means that we exist for the country, and it's in the history books. It's scary! But it's also exhilarating.

MW: And then the fact that he's also the first African-American president….

JONES: Yes, and knowing the rampant problems of homophobia in the African-American community. This is the man who mentioned God – well, he mentioned God more times than I would. I don't think God has a place in politics. But he does. So, he's a father, he's a God-fearing man. And he has made room for this concept in his world. What does that mean for other black folks? How is it playing in the churches now? Because you know we all had his back. Didn't he take something like 93 percent of the black vote?

Now what percentage of that black vote is against gay marriage? Or has this biblical sense that gay marriage is an abomination? I know I have it in my family. I know I have people in my family who I can't talk to now because they've been told by their pastors they cannot communicate with me. What does it mean that the president said that yesterday: ''gay brothers and sisters.'' Yeah, it was a big thing. And on Martin Luther King's Day. It was all very self-consciously done. Nothing this White House does is not thought through. You can fault them for that or praise them – I accept it. I think it's just the way we have to behave in this media-tized, political era we find ourselves in. But, how is it playing now in all the constituencies? He kept saying, ''We the people.'' That ''we'' now includes me and my companion.

MW: And now people who go against you are going against the president. They have to factor that into their views now, to at least a certain degree.

JONES: Yeah, they do. And then we have to think about the president and his symbolic role. This president who represents the state of our democracy. Doesn't he in a way? So it's not being against the man personally, but it's against this democracy. This man who represents us has said that ''we" has gay people in it. Now, are they going to be against that? But, yeah, we'll see how it plays.

But also, what about climate change? What about the immigration issue? What about more money toward rebuilding infrastructure and education? Those are incredibly important. And he was articulating it in a very clear way. Yes, it did feel political. I don't agree with the Republicans who say it was divisive. That's absurd. But it was actually laying out, this is what our moment is. What are you going to do about it? That I found really exciting. But nothing was as exciting as the gay and lesbian.

Bill T. Jones with Arnie Zane

(Photo by Louis Greenfield)

MW: Let's switch gears a bit. I wanted to ask you to reflect on your work on Broadway, from winning your first Tony your first time at bat, with Spring Awakening, to winning a second Tony, also for choreography, a few years later with Fela!, which you also co-wrote and directed.

JONES: In some ways I've had a really wonderful path into commercial theater. With Spring Awakening, I was shown great respect being an outsider on Broadway. They let me do things that did not normally happen on Broadway. [With Fela!, producer] Steve Hendel asked me to help write it and direct it and choreograph it, and he made every resource available to make the work that I needed to make. That was, people tell me, an atypical introduction to Broadway. And I respect it. I'm very, very pleased.

I'm now working on another show – I won't tell you the name of it, but it's also dealing with rhythm and blues in the '70s. With another producing team, with in some ways a more conventional producing approach. But nonetheless heartfelt, and they really want me to do something adventurous and exciting. We're hoping to make some money, because you know that's what it's about. And it's exciting that there are other projects open for me. Now, the problem is how do I make things like A Rite with my company, and at the same time pay the piper on the work-intensive Broadway work? That's one of the dramas in my life. Not to mention that I'm executive artistic director of a downtown performing arts space called New York Live Arts, which is a re-imagining of the historic Dance Theater Workshop and Bill T. Jones/Arne Zane Dance Company. That's three fronts – all of them demanding, and all of them rewarding. So, stay tuned.

MW: Any sense of when that next Broadway production you mention might see the light?

JONES: Well, I hope that we're ready to go by next season. I hope that we're able to – the show's going to be going to its final rehearsal in the development phase in June. We'll work on it throughout the summer and into the fall. We'll reconsider it, and then probably open somewhere in the late winter or spring next year. Now, that's what we hope. Let's not jinx it. But that's what we hope.

MW: So in the next couple years at least.

JONES: Oh, yes. Hopefully in the next year actually.

MW: The success on Broadway has also offered you even wider, national recognition, such as a guest appearance on The Colbert Report in 2009, promoting Fela! That must have been a trip.

JONES: [Laughs.] That was a singular night! It was quite fascinating. It all went so fast. I've never done that show. Stephen Colbert's people told me, ''Look, don't try to compete with him being funny. This is what he does.'' And that was very good advice. He's outrageous, but he was very respectful of us and Fela!

MW: And you pulled it off with aplomb, at least from a viewer's perspective. You held your own.

JONES: Yeah. And another one like that is Bill Maher. I had been on Maher's show when it was called Politically Incorrect, and now and again. Both of those guys are kind of heroes to me, with what they take on.

MW: Ten years ago, could you have imagined your work on Broadway, even going so far as co-writing and directing a musical?

JONES: Well, 10 years ago was almost when Steve Hendel first brought the Fela! idea to me. But hmm, no, at that time, it was all kind of a lark. It was, why not? You've tried this, you've tried that. Let's give this a try. But don't give too much of yourself to it. Which is impossible. I give 100 percent to everything that I do. But let's just see – let's play at it. Don't lose yourself in it.

MW: But do you feel like, even with all your commercial success, particularly on Broadway, you've managed to maintain your own individuality and integrity? Do you feel like you've sold out in any way?

JONES: Well, I don't know what ''sold out'' actually means. I am kind of hard-headed. And I have a lot of baggage that comes with me. And anybody who works with me knows there's a lot of baggage, and I have a history. I am very visible as a gay man, I'm very visible for things that I have made. And so if a producer asked me to do something, they certainly know something about what they're getting. My goal is to surprise myself, and not get into battles about everything that I do. I have this belligerent, ''don't tell me what I can do'' attitude. It's not an easy ride. I keep trying to find the way to make the best work I can make – not an embarrassment. And by the same token, to make some money – for myself and my producers. I think they deserve it.

MW: Are there other big things you're working on, ways you're striving to surprise and challenge yourself anew?

JONES: Right now, the company opening at the Joyce Theatre in New York in April. It's going to be two evenings, all built around music. We're going to be working with a wonderful quartet, the Orion String Quartet, the Lincoln Center chamber orchestra. And we will be doing musical works that go back probably 15 years, maybe even more. That's very exciting because we'll have live music at all of those.

I'm planning even deeper into the future. There are things that come at me every day, but it would be immodest to be playing them all out. I'm planning at least two musicals stretched over the next 10 years of development. And the company always needs to be fed. New works, new ideas. The next thing the company does will be something that could very well be a play that I have been given, that has dance in it, about George and Martha Washington. But once again, well, I'm sure you'll hear about it.

A Rite is Friday, Feb. 8, and Saturday, Feb. 9, at 8 p.m.,

at Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center's Kay Theatre, University of Maryland, University Boulevard and Stadium Drive, in College Park. Tickets are $50. Call 301-405-ARTS or visit claricesmithcenter.umd.edu.

Fela! 'runs to Feb. 10, at the Sidney Harman Hall, Harman Center for the Arts, 610 F St. NW. Tickets are $25 to $130. Call 202-547-1122 or visit shakespearetheatre.org.

For more information about Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company or New York Live Arts, call 202-691-6500 or visit newyorklivearts.org.

...more