Setting the Stage

TWO YEARS AGO, under the guidance of artistic director Paul Tetreault, Ford's Theatre launched the Lincoln Legacy Project to annually build programming that educates and engages on topical issues, all centered on a particular theatrical production. In 2011, the project debuted with Parade, the play by Alfred Uhry dramatizing the 1913 trial of a Jewish factory superintendent in Georgia accused of raping and murdering a 13-year-old employee. Ford's complemented the staging with discussions of anti-Semitism, of relationships between African-American and Jewish communities in the South, and other points of interest stirred by Parade.

The next year, Ford's chose Trey Ellis and Ricardo Khan's Fly, based on the World War II experiences of African-American pilots. This 2012 iteration included an exhibit, The Test, in Ford's new Center for Education and Development across from the theater on 10th Street, detailing the training of these pilots and the racism they faced.

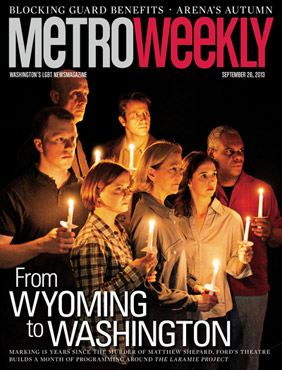

Now, Ford's is turning to Matthew Shepard, the 21-year-old gay man beaten, tied to a fence and left to die in Laramie, Wyo., 15 years ago. And it's all coming together at a time when the basic narrative is again being challenged. In 2009 it was Rep. Virginia Foxx (R-N.C.) calling the hate crime a ''hoax.'' Today, it is Stephen Jimenez's new book, The Book of Matt, claiming that methamphetamine rather than bigotry was central to Shepard's murder, for which Aaron McKinney – who attempted to use the dubious ''gay-panic defense'' – and Russell Henderson were convicted. Clearly this is a story that is tightly woven into the American cultural fabric. It's a true story that has changed a family, a town and a nation forever. How fitting, then, for Ford's Theatre, the spot where President Lincoln was shot, to focus its third Lincoln Legacy Project program on The Laramie Project, the play by Moisés Kaufman and members of the Tectonic Theater Project, exploring the reactions of the people of Laramie to the murder that made their home the nexus of national debate on hate crimes, on LGBT equality, on American values.

As with Parade and Fly, the programming goes far beyond the staging of the play itself. There will be Monday-night discussions, Sunday readings of the companion play Ten Years Later, an exhibit featuring many of the thousands of letters sent to the Shepard family, a candlelight vigil and more.

''The formula we've worked with, including this year, is we create this community conversation around the piece,'' Tetreault explains. ''It is an event. It is a huge event. … It would be nice for Ford's to just put on The Laramie Project. But why? Why just do that? Why stop there? We have a platform in Ford's Theatre, in Abraham Lincoln, in his legacy, in this education center. We have a platform to create a dialogue for Americans to talk about these issues.''

Finding Direction

Matthew Gardiner

(Photo by Christopher Mueller)

MATTHEW GARDINER KNOWS knows exactly where he was when he learned of the murder of Matthew Shepard in October 1998. Fourteen at the time, he was seated in the backseat of his parents' car, fighting with his twin brother, James. Their mother was in front listening to the radio as they sat parked, waiting for their father to return from an errand. Then, their mother turned in her seat to face her sons – particularly Matthew. She was crying.

''It doesn't matter who you are, I love you no matter what,'' the 29-year-old Gardiner says, repeating his mother's words. ''I started to listen to what they were talking about on the radio, and they were talking about Matthew Shepard.''

''It had both a positive and a negative effect on me," he continues. "The positive effect was the words that came out of my mother's mouth stayed with me till I came out. The negative was being a 14-year-old and hearing about the attack on a young gay man. It delayed my coming out. It was terrifying to a young, gay kid to think that could happen to someone. Or that could happen to me.''

Today, Shepard's murder is again influencing Gardiner's life. Gardiner, associate artistic director at Arlington's Signature Theatre, is stepping into Ford's Theatre to direct this production of The Laramie Project. And while Gardiner has directed serious, intense material before, this play brings its own challenges, both technical and emotional.

''Laramie is a series of monologues,'' Gardiner says. ''There are very few moments in the play when people are actually engaging with other people on the stage. The challenge is, when it's a play about a community, how do you create a community? How do you make this group of actors feel like a community when they're never looking at each other? We spend a lot of time in rehearsal when I'll say, 'Okay, turn to this person and deliver this monologue. Now turn back out. And all of a sudden, it irises things down, it becomes very specific. It's a different thing when you're saying this monologue to a woman instead of a man. It's a different thing when you're saying this monologue to somebody in their 50s, as opposed to someone in their 20s. So it's a lot of figuring out what are your opinions and who are you talking to. When it starts to feel like we're talking to a wall again, we turn back to the person and we try to find what it is like to actually speak to another person onstage and not just deliver another monologue.''

The emotional punch, however, seems to have been the greater challenge, at least when rehearsals began.

''Those early rehearsals were hard,'' Gardiner readily admits. ''Everybody would end rehearsal in tears. At some moment, we were like, 'We cannot do this for three-and-a-half weeks.'''

Gardiner and his cast may have managed to find ways to create some personal distance from the material as they continue to master it, yet there is no getting around the gravity of not only the play itself, but the monumental nature of staging this play in this theater, representing the living residents of Laramie to audiences that will range from Shepard's family – even if Matthew's mother, Judy Shepard, finds it possibly unbearable to sit through a full staging – to a range of D.C. luminaries, marking this sad but important anniversary.

''I can't let myself think that way,'' says Gardiner. ''Otherwise, all of my decisions and choices will be hindered. All I can do is honor the voices in the play and do my best in that. There are just a lot of people that are committed, who believe that this story is still important to tell, both for Matthew Shepard and the community of Laramie, Wyo. – and for the gay, lesbian, bi and transgender community of D.C. There are a lot of people we feel it's important for. I try not to get stressed out about all of what's around it.''

Exhibiting an Outpouring

Paul Tetreault

(Photo by Scott Suchman)

WHILE GARDINER AND his cast and crew prepare the stage production, others have given attention to the complementary exhibit now open in Ford's Center for Education and Development, Not Alone: The Power of Response. Almost by accident, the nature of the exhibit was a sort of gift from Judy Shepard.

Months ago, in late winter, Tetreault was sitting in a conference room in the center, discussing with Judy Shepard the programming that would revolve around The Laramie Project. Sitting at the same table where the two spoke, he tells the story these months later.

''I said, 'We have this gallery space downstairs and we'd really like to do something great with that,''' Tetreault recalls telling Judy Shepard. ''And she said, 'Well, you know, we have these letters. After Matthew's beating and murder, we got over 10,000 letters and cards. They're in the basement of our home in Casper and no one's ever seen them. You can have access to those.'

''That meeting, in this room, is where that exhibit was born. We sent a team of four people to Casper, Wyo., shortly after that.''

Heading that team was Tracey Avant, Ford's curator of exhibitions, who found herself in a somewhat surreal setting, standing in a storage room off the Shepards' finished basement, facing several boxes of correspondence and other materials related to Matthew Shepard's death and the response it generated – a very sizable response.

''They had these tubs, bins stacked up with the materials,'' Avant explains of her expedition to Casper. ''We knew going in there would be about 10 of these bins filled with letters. Someone had gone through them when they got donations and things like that, but they weren't organized in any particular way.''

Avant and her team set to work there in the Shepards' basement, reading the letters, making high-resolution digital scans, keeping an eye on what might be appropriate for an exhibit back in Washington.

The most surprising find, Avant says, wasn't in anything they discovered, but what they did not.

''The biggest thing I took away from this experience is that when these things happen, you realize that more people are compassionate and caring and understanding than not,'' she says. ''In the course of these 10,000 letters, they probably received less than a handful of hate mail, which to me was shocking. I would've assumed that there would've been a lot more.''

There was also something notable in that this sort of experience is rare for a curator, says Avant, with the ''history'' in question still relatively recent, still actually unfolding.

''These people are alive, we spent time in their house,'' Avant says of Dennis and Judy Shepard. ''That is a really unusual experience. And they are the most amazing and warm people, welcomed us into their home. You go into a situation like that with trepidation. You don't want to impose. They've invited you to do this, but you're in their home, their personal space. So to be able to work with material like this, that you have a real human connection with, especially doing history exhibits, it's rare that you have that kind of modern history. I'd never had an opportunity to do that. It's been pretty emotional and amazing.''

What Ford's has created as a result is also emotional and amazing, with letters suspended behind glass in a space that is otherwise unassuming, with only a few benches. Avant says this is the first exhibit that's prompted the center to leave boxes of tissues on those benches. But some letters will likely elicit a strong response – maybe not the two from Bill Clinton, or some of the other similarly stately messages, but certainly those written by children or just everyday people compelled to respond with some positive action to the hate and violence that killed Matthew Shepard.

Avant mentions one of her favorite examples.

''There was a young woman who wrote from New York shortly after, saying that she was going to start this tennis tournament, this 'Tennis Jam,' and send the proceeds,'' Avant says. ''Then we have her follow-up letter from almost a year later when she sent the proceeds. She actually managed to follow through, do the tennis jam, and send the money from that.''

New Yorkers – particularly tennis-loving LGBT New Yorkers – might recognize that event as the Metropolitan Tennis Group's Matthew Shepard Memorial Tennis Jam, marking its 14th year Oct. 13.

Letters aside, however, there is another element of the exhibit, one standalone feature that is equally as powerful. And it was also Judy Shepard's suggestion. Tetreault, in his discussions about the exhibit with Judy Shepard, pointed to the bare wall running the length of the room opposite the display of the letters. She suggested a photograph: ''Where Matthew Lay Dying,'' by Jeff Sheng. As visitors walk into the exhibit space, they face an expansive vista of snowy plains, wooden fencing in the foreground. The view is simultaneously beautiful and terrifying, sharing the point of view from where Matthew Shepard was tied to that lonely fence.

With these elements paired, one imagines Ford's will be replacing those boxes of tissues with some regularity.

''This exhibit is revelatory,'' says Tetreault. ''This is something that no one else has ever seen before. These have been in Dennis and Judy's basement for 15 years. Judy created the exhibit, I just executed it. It was her idea. It is extraordinary.''

A Legacy for the Future

THE LINCOLN LEGACY Project is essentially Tetreault's brainchild, one for which he says there was great support among Ford's Theatre backers. And from the start, he knew he wanted The Laramie Project to be part of it.

''I've kind of had The Laramie Project on my radar since we started the Lincoln Legacy Project three years ago,'' he shares. ''I knew I wanted to do a project, a piece that centered on gay issues, on gay-rights issues and what those were. That leaves you a realm of things. Then thinking about Laramie and thinking about the 15th anniversary and how that plays out. I thought that was a great time for us to look at that.''

He points to Jason Collins, the gay basketball player who chose to wear a ''98'' jersey as a memorial to the year Matthew Shepard was killed, and to the work of the Matthew Shepard Foundation as contemporary elements that remind him of the importance of the crime 15 years on, and the importance of revisiting it with the Lincoln Legacy Project.

Tetreault adds that this third iteration is evidence that the project's expected five-year run at the time it was launched has given way to new ideas of making it ever richer, and with no end in sight.

''We've stopped using the term 'five-year.' We think it will just be an ongoing program, because we've got issues,'' he says, smacking the table for emphasis. ''This country has issues that it needs to talk about. If they're not going to talk about them in the town square, I'm going to talk about them on the Ford's Theatre stage.

''There's no shortage of subjects we need to talk about. The question is making sure you find a quality piece of theater that fits at the center to have that dialogue. If you can't do high-quality work at the center, you'll lose anyone's interest in following the conversation. You have to do the highest-quality work at the core, and then you can actually have a dialogue.''

The question of that dialogue prompts two further points from Tetreault. One is his understanding of his audience. Pointing to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.), for example, as a regular Ford's Theatre attendee, Tetreault says that Ford's offerings have the opportunity to influence America's leaders, to perhaps challenge some negative ideas and encourage positive ones. At the same time, he points to the challenge of taking Ford's Theatre's content and moving beyond the confines of geography, enabling all Americans – if not a global audience – to join the discussion. Live-streaming a post-show interview with Judy Shepard is one of Ford's steps in that direction.

What Tetreault seems most passionate about, however, is his dedication to honoring Abraham Lincoln. The Lincoln Legacy Project is by no means an effort in name only.

''The mission of Ford's Theatre is to carry on the legacy of Abraham Lincoln,'' he says. ''I think that creating a dialogue in this Lincoln Legacy Project, which is to deal with issues of tolerance, equality…. Lincoln said, 'With malice toward none, charity for all.' That's what this is. That's what the Matthew Shepard Foundation is about. Lincoln said, 'for all.' And that is what we're doing. To me, this Lincoln Legacy Project, which is slowly becoming a sort of cornerstone for who we are and what we are, I think, is exactly what we should be doing, because it is, at its core, the essence of who Lincoln was.''

''I think Abraham Lincoln would want to see this play," Tetreault concludes. "I think he would like to hear this story. And that is my guide. It's always my guide. I think, 'Where would Abraham Lincoln stand on issues of anti-Semitism?' We know where Abraham Lincoln stood on issues of race. 'Where would Abraham Lincoln stand on GLBT issues today?' I have no question. If anyone does question that, then they just don't know Abraham Lincoln.''

The Laramie Project as part of the Lincoln Legacy Project runs from Sept. 27 to Oct. 27 at Ford's Theatre, 511 10th St. NW. The exhibit, Not Alone: The Power of Response, runs to Nov. 3 at Ford's Center for Education and Leadership, 514 10th St. NW. For more information about either, or to purchase tickets, call 202-347-4844 or visit fordstheatre.org.

...more