It's the one area of public policy that still prompts giggles and bad jokes about junk-food cravings, but the push to reform the nation's laws on marijuana is growing. Much like marriage equality, attitudes about the drug are rapidly shifting, with proponents of decriminalization and legalization in ascendancy. And in light of voter-approved ballot measures that legalized small amounts of the drug in Colorado and Washington state, it is inevitable that Washington, D.C. and Maryland will soon be faced with a decision regarding how to deal with and treat marijuana-related offenses.

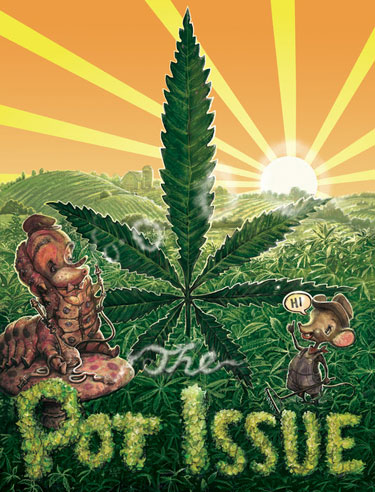

(Illustration by Scott G. Brooks)

Under federal law, using or buying marijuana has, for all intents and purposes, been illegal since 1937 when Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act. But even though marijuana has a long history of medical use, the United States only began acknowledging any health benefits -- and only to a very small, very restricted group of people -- in the late 1970s. It was only after advances in cancer and HIV/AIDS treatment that health practitioners began noticing the positive effects for those suffering from serious illness.

California became the first state to legalize marijuana for medical use, via a ballot initiative in 1996, followed by Alaska, Oregon, Washington state and Washington, D.C., two years later. Yet even though D.C.'s referendum for medical marijuana passed in all eight wards of the city, congressional interference attempted to initially prevent those votes from being counted. After they were -- with the pro-marijuana side winning 69 percent to 31 percent -- Congressional oversight still prevented the District from implementing the law for more than a decade.

HEMP AS HEALER

It was the scourge of the HIV/AIDS epidemic that first convinced Pat Hawkins, a longtime clinical social worker, psychologist, and former substance-abuse treatment counselor, to support medical marijuana.

"For some patients, it eased their dying," she says. "I had patients who were literally wasting away before my eyes, and I was sending out these 85- or 95-pound weaklings out on the street to 'score some weed.'"

While Hawkins could not purchase the drug for her patients or accompany them when they went to buy from local drug dealers -- under the threat of losing her license -- she decided to partner with other concerned citizens to draft legislation that would allow her patients and others suffering from debilitating illnesses to obtain the marijuana they needed, often essential to reducing nausea and restoring appetite for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, or HIV/AIDS patients who were suffering from the toxic side effects of the earliest antiretroviral medications.

"It was very risky," she says of the dangers her patients navigated to get some relief. "Depending on who busted you, you could end up dying in jail."

Hawkins particularly credits former director of the Whitman-Walker Clinic and current D.C. Councilmember Jim Graham (D-Ward 1) with leading the way on the fight to get medical marijuana to the ballot. She says she and other activists knew that Congress would likely try to block the law, but pushed on, feeling it was in the best interests of the District's residents who were suffering.

"I feel very strongly about medical marijuana because I've seen it work with people who have severe pain -- not just headaches or whatever -- without them having the side effects of the major pharmaceuticals," she says.

Pa tHawkins: Capital City Care

(Photo by Todd Franson)

As opponents often conflate medical marijuana with outright legalization of the drug, Hawkins says she heard similar opposition, particularly from religious groups, when D.C.'s activists were first proposing legalizing medical marijuana.

"The opposition to marijuana has been so associated with the '60s that a lot of conservatives just lumped it together with anti-patriotism, the anti-war movement, and the sexual revolution," she says. "I also think because so many of the advocates for it have seen it as a step in achieving a long-range goal of legalization, the two issues have been confused. Personally, I have never been a rabid fan of legalization. My long-range goal was to get medical marijuana."

Hawkins adds that with the progression of HIV/AIDS, a lot of the opposition, even from religious communities, eventually "melted away."

Since D.C.'s referendum passed, 16 more states have legalized medical marijuana, while South Dakota rejected a proposed ballot initiative in 2010. The District also finally had medical marijuana legalized in 2010 after a Democratic-controlled Congress declined to overrule a D.C. Council bill to establish a network of dispensaries and cultivation centers that would closely regulate and monitor patients who are prescribed medical marijuana for certain conditions. Those conditions are limited to: cancer, HIV/AIDS, glaucoma and multiple sclerosis or other muscular-related ailments that interfere with the basic functions of life.

Under District law, patients may possess up to two ounces of the drug, in dried form, but must obtain it from a licensed dispensary and must carry a card from the Department of Health, which oversees implementation of the medical marijuana law, confirming the medical marijuana prescription just to gain access to the dispensaries. Three dispensaries began treating patients in July 2013, though owners of the dispensaries have complained to media outlets about low demand due to the law's many restrictions.

Those restrictions are quite familiar Jeffrey Kahn, a Reform rabbi who, along with his wife, one of his sons, and daughter-in-law, operates the Takoma Wellness Center, one of the city's three operating dispensaries and the only one that's owned and operated by a single family. Kahn says the Department of Health is quite serious when they say they track the merchandise he offers "from seed to stem." He says that officials from the D.C. Department of Health (DOH) the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) regularly check up on the store, with DOH's pharmacy division able to access his records and keep track of the dispensary's sales and deliveries.

"It's an unspoken arrangement that this is going to be done right," Kahn says of the program. And he says it's going fairly well, though he's been exasperated by the slow rollout of the medical marijuana program because he wishes he could help more people. But he also understands that District officials want to be cautious.

"Even if we do everything right, the Department of Health needs to, too," he says.

Like Hawkins, Kahn was first introduced to the medical marijuana movement through his contact working with sick people, particularly those suffering from HIV/AIDS.

"I was ordained on June 5, 1981, the day the morbidity and mortality rate was announced for the very first cases of AIDS," he recalls. "And I was in a position to minister to those affected by it, and learn what was happening."

"My own first experience with medical marijuana was related to me by someone whose brother was dying of AIDS, who told me, 'Rabbi, he just seems in so much pain, so withdrawn, that I lit up a joint and blew it in his face.'"

The person told Kahn that the brother's pain seemed to subside quickly after that, and the brother -- who had not been able to eat -- wanted to order a pizza. They did, he ate one slice, and then fell asleep for two hours, the first restful sleep he had enjoyed in months.

Takoma Wellness Center: Rabbi Jeffrey Kahn

(Photo by Todd Franson)

Kahn says he first broached the idea of getting licensed to operate a dispensary after testifying before the D.C. Council in February 2010.

"I met with my family and said, 'I think this is something we can do,'" he recalls. "The whole family was excited about it. We enjoy helping people, seeing dramatic and miraculous stuff happen. ... The patients seems healthier and say they feel better when they come in after their initial visit, and they often use less [marijuana] as they get stronger."

Kahn says his dual roles as both a rabbi and medical-marijuana pioneer raise a few eyebrows, but not too many.

"From a Jewish perspective, healing and bringing comfort to the sick is the most important thing," he says. "Some people are a little taken aback, but it's not as if the Jewish community would be as shocked about a rabbi working with medical marijuana as they would if a rabbi were the world's biggest bacon producer."

As he walks around the dispensary, Kahn adjusts some of the displays offering various strains of medicinal marijuana grown by the city's three operating cultivation centers, paraphernalia or other devices like those used for vaporization or "magical butter" machines that infuse cannabis into soluble fats, which can then be used to cook edible treats. The atmosphere of the actual "store" part of the dispensary is like a mom-and-pop store counter, where patients can obtain the amount of product they need, while the remainder is run like a doctor's or social worker's office, with space allotted for screening and tracking patients' progress.

Initially -- and even to some extent even today -- medical marijuana has been misunderstood, with opponents of medical marijuana raising the specter of open-air drug markets and unregulated chaos. But Kahn says D.C.'s program is so closely monitored and its standards for qualifying to take part in the program are so strict that it deflates any scaremongering or visions of underground smoke shops that would rival Amsterdam.

"For 70 years, we've been teaching people negative things about marijuana," Kahn says. "But because diseases are equal opportunity employers, more and more people know someone who's been touched by medical marijuana. And these are regular, average, normal people. Most of our patients are older, and probably wouldn't feel comfortable in a counterculture-type establishment anyway."

Still, it's that high degree of regulation that concerns Hawkins, who voices concerns that the limitations placed on medical marijuana mean that some who could truly benefit from it are not.

"I'd say the law is not working very well, because so few have been able to register," Hawkins says. "They have to go through the Department of Health, which is slow and obsessed with the bureaucratic process, which makes some patients distrustful of the program."

In addition, she adds, many doctors are leery of prescribing medical marijuana at all, because those patients seeking to register under the new law have to have their primary doctors sign a piece of paper that states that marijuana possession and use is still illegal under the law and spells out the legal ramifications of breaking the law. A better solution, she says, would be to amend the law to allow the primary doctor to refer the patient to another doctor if they are uncomfortable issuing the prescription for medical marijuana themselves, rather than intimidating doctors and deterring them from recommending marijuana for those that truly need it to treat chronic conditions.

Hawkins says she saw a similar scenario take place when D.C. began its clean needle exchange to reduce the rate of transmission of HIV through intravenous drug use, in 1991. The program, which was run with strict controls through the Department of Health, only managed to register 26 people in the first year. However, once the program was moved to the private Whitman-Walker Clinic (now Whitman-Walker Health), the rate of participation increased. Hawkins was later forced to set up -- within a span of three days -- Prevention Works, a nonprofit organization, to take over the administration of the needle exchange and transfer all the program's assets, after outgoing President George H.W. Bush issued an executive order barring places engaging in needle exchange from receiving federal funding.

In that way, Hawkins believes marijuana will follow a similar trajectory, with dispensaries, like Takoma Wellness Center, seeing more customers and losing less money if a private firm takes over the administration of the program. Hawkins also believes that other changes are needed to expand the program beyond a small population that experiences one of the four required medical conditions. Her hope is that the D.C. Council will pass legislation to amend the current law to instead use the restrictions as guidelines, rather than absolutes, for the types of conditions that can be treated with medicinal marijuana.

For example, she says, people officially diagnosed with severe "debilitating" migraines, children suffering from pediatric epilepsy, and people who suffer pain after having limbs amputated could benefit from medicinal marijuana, but are currently unable to enroll in the District's program.

"None of the dispensaries will survive if there aren't more patients," warns Hawkins.

RALLYING FOR RECREATIONAL USE

It is against this backdrop that the fight over non-medicinal marijuana will take place in the District. While Mayor Vincent Gray (D) has indicated he is supportive of the idea of decriminalizing marijuana possession, as recently as the past summer, his office has reported that the mayor thinks D.C. government should focus its efforts on implementing the District's medical marijuana program before attempting more difficult goals of decriminalization or legalization.

Still, led by councilmember and mayoral candidate Tommy Wells (D-Ward 6), the D.C. Council is poised to vote as soon as Feb. 4 on a bill that would decriminalize, meaning lessened penalties, for those caught possessing marijuana. Under current District law, the penalty is a fine of $1,000 and up to six months in jail. Under Wells's bill, that fine would be reduced to $25.

Proponents of the measure -- a clear majority of the 13-member council, though with varying degrees of enthusiasm -- say that the legislation is needed to combat racial disparities among people arrested for marijuana possession. As currently written, the bill also includes a fine of $100 for people caught smoking marijuana who do not identify themselves at a police officer's request, and a separate fine of $100 for smoking marijuana in public. But even if the bill passes and receives Gray's signature, it will have to pass a 60-day congressional review period during which Congress could choose to overturn or halt the law.

At the same time that Wells's decriminalization initiative is receiving a vote in D.C. Council, other D.C.-based marijuana activists are pursuing a ballot initiative that would make it legal to possess up to two ounces of marijuana, grow up to three plants at one's home, and transfer up to an ounce of marijuana to another person. In order to appear on the ballot, the referendum would have to be approved by the D.C. Board of Elections and Ethics, weather potential challenges to its wording, and gather petition signatures from at least 5 percent of D.C.'s registered voters -- including at least 5 percent of registered voters in five of the city's eight wards. Then, if enough signatures were determined to be valid, voters would have to approve the measure, which, again, would be subject to congressional oversight.

But legalization is not a foreign concept to the D.C. Council. Last September, Councilmember David Grosso (I-At Large) introduced a bill that would legalize, regulate and tax marijuana -- at 6 percent for the sale of medicinal marijuana, but 15 percent for all other uses -- but that bill has largely been sidelined in favor of Wells's decriminalization measure.

Additionally, if opinion polls are to be believed, the public is highly supportive of not just decriminalization, but full legalization. A January Washington Post poll of 1,003 adult D.C. residents found that 63 percent support full legalization. Meanwhile, 16 percent oppose legalization, but support decriminalization. Only 17 percent saying they both oppose legalization and oppose or do not have an opinion on decriminalization.

Even so, support for decriminalization -- not to mention legalization -- is not universal. Metropolitan Police Department Chief Cathy Lanier has said decriminalization is worthy of "robust discussion," but has also alleged that arguments in favor of decriminalization are "flawed."

Substance abuse prevention groups, such as the Alexandria-based international Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (CADCA), fiercely oppose legalization, going so far as to criticize President Barack Obama for comments he made in an interview with The New Yorker that he believes marijuana is no more dangerous than alcohol, even though he also said he'd discourage his daughters from using the drug.

"CADCA is concerned that only a portion of what the President said during his interview has made headlines, when in fact the President expressed some serious concerns about marijuana legalization," Gen. Arthur T. Dean, chairman and CEO of CADCA, said in a Jan. 23 press release. "CADCA believes that substance abuse is a public health concern and has wide-reaching negative effects on our young people and society. So we agree with President Obama's comment that marijuana use is a 'bad habit,' a 'bad idea and a waste of time.' We also echo the President's sentiment that the case for marijuana legalization is 'overstated' and will not solve the many social problems our society faces."

"The President also noted that the marijuana legalization experiments in Colorado and Washington might create a 'slippery slope' where people begin suggesting that we legalize harder drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine," Dean continued. "CADCA couldn't agree more."

Regarding legalization, political observers should keep their eyes on the gubernatorial campaign of Maryland Del. Heather Mizeur (D-Montgomery Co.), who has proposed legalizing, taxing and regulating the substance in order to generate the revenue needed to pay for universal pre-kindergarten for all Maryland children, while reducing what the state spends on incarcerating some people convicted of possession of marijuana.

Under Mizeur's plan, adults 21 and older would be permitted to possess up to an ounce of marijuana and up to five grams of concentrated marijuana. Smoking in public, or driving while under the influence of marijuana, would remain illegal at any age. Mizeur also proposes a range of fines and jail times for those caught breaking such laws or those seeking to traffic marijuana. Minors caught possessing marijuana would be fined, and could be required to submit to drug and alcohol counseling.

On the tax side, Mizeur's plan imposes a $50 excise tax per ounce at the point of sale between cultivators and retailers, and a 6 percent sales tax and 2 percent excise tax on those purchasing marijuana from retailers. According to Mizeur, if the estimated price of a gram is $7, Maryland could expect to generate between $122.5 million and $157.5 million.

But Mizeur also acknowledges that her state might not be ready to automatically embrace legalization, largely because Maryland is still playing catch-up on other fronts related to marijuana.

"We do have a medical marijuana law, but it's rather conservative," she says. "It passed last year, and it hasn't been implemented in the way everyone had hoped. The sponsor of the bill is coming back this year with revisions that will put it more in line with what other states have done."

On whether decriminalization is necessary before tackling legalization of the drug, Mizeur says, "I don't think it has to come first, but I do acknowledge that it might take an election to get a mandate from the voters, to change old ways of thinking about this in Annapolis. At a minimum, we're going to need a Mizeur-Coates administration to get legalization passed."

Regardless, Mizeur is has sponsored a bill aimed at decriminalizing marijuana.

"At a minimum, we need to leave this session having reformed the laws so people's lives aren't ruined and entangled in our criminal justice system unnecessarily," she says of her priorities.

So, while legalization won't be taking effect soon, both the District and Maryland are likely to become ensnared in the debate over the effectiveness of decriminalization and whether the policy achieves its intent.

"Given what's happened in Colorado and Washington, I think that's the path we're on," Hawkins says of the District's progress toward more liberal marijuana laws. "But any changes to our medical marijuana program, or decriminalization will have to be able to get through Congress. Adding something like drug and alcohol counseling or treatment for those who do get caught with marijuana to a decriminalization bill might make it easier to pass, because people can become psychologically, if not clinically dependent."

...more