There is no argument: Lily Tomlin loves show business. And that love has driven her from stage to screen and back again, countless times.

With her partner -- in life and profession -- Jane Wagner at her side, Tomlin has earned an Oscar nomination, multiple Emmys and Tonys, and so many more accolades. She's played characters from silly -- many of whom are her own creations -- to serious. There's the young Tomlin of Laugh-In yuks, or the grittier Linnea of Nashville. She's shared the screen with Cher, Bette, Jane and Dolly, to name a few. From the frantic battle to grasp the dawn of the AIDS epidemic as Dr. Selma Dritz in the movie version of And the Band Played On, to animated voiceovers, there is range, there is talent and there is dedication.

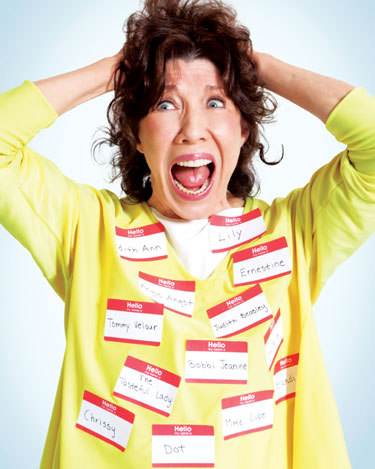

Lily Tomlin

(Photo by Jenny Risher)

"We're forever wanting to make something," she says of Wagner and herself, offering as an example an effort to produce a show based on Tomlin's precocious 5-year-old persona, Edith Ann. "One time we really wanted to get a series together for Edith Ann, and we wanted to do it in claymation. This was -- oh, God, I don't even know -- before claymation was very popular. And 3D was really prohibitive. We built Edith Ann's whole neighborhood in our garage with clay animators. We could not convince anyone to do dimensional animation like that at the time. It must've been 30 years ago or more.

"And we've done that many times. It didn't matter. You're just so mad to make something that you don't think twice about it."

It's been like that since Tomlin, 74, was not much older than Edith Ann, trying -- unsuccessfully -- to corral her neighborhood peers of inner-city Detroit to put on a show. With an Edith Ann-inspired raspberry to whatever stands in her way, Tomlin has not been deterred, which is why she'll soon be back in the D.C. area for a show. And in Florida for two. And Las Vegas. And an Olivia cruise. Tomlin long ago found the secret to making magic, and she's not about to stop.

METRO WEEKLY: You're back in L.A. for a few days? I'm told you've been doing some filming. Can you tell me what you're working on?

LILY TOMLIN: I was doing a thing for a friend that was just sort of fun. Rocco Urbisci was the producer on a couple of my specials years ago, for one of which we won an Emmy. Anyway, Rocco manages these two young girls that are really interesting. They do kind of satiric songs and comedy. Their names are Carlie and Doni. They'd written a song called "Gangsta Waitress." It's really funny, and they were making a music video of it. I played their, like, top waitress.

MW: A recurring role for you.

TOMLIN: Oh, yeah, right! [Laughs.] But just for this little video. It was hip, dirty, campy and all of that.

MW: But early on, you actually worked as a Howard Johnson's waitress?

TOMLIN: Oh, God, yeah, I did. I worked at the old original one at 49th and Broadway, which was like the first Howard Johnson's in New York. It was a little, tiny, narrow storefront. It wasn't very big. Their bigger one was down near 52nd Street and Broadway, then the big one across town was the HoJo hotel. Mine got shut down. We were not even on the circuit. I don't think the Howard Johnson's people who came to inspect even came to our restaurant. We had really old uniforms, like from the '30s, that were so starched. Their uniforms would stand on their own because of so much starch. We were all wannabe actresses and everybody wanted to be really attractive, so the other girls would hem 'em up real fast every morning, so they could be wearing miniskirts. [Laughs.] I always wore mine totally regulation. Tall and lanky. But those uniforms were cut on the bias and you were supposed to have a lot of hips. Of course, I didn't. You had these big, puffy sleeves and your little arms are hanging out. It was like playing a role. I wanted to be a real Howard Johnson's waitress. I'd wear a hairnet and a paper hat.

I used to duck down behind the counter with a microphone and I'd say, "Attention, diners. Your Howard Johnson's 'waitress of the week,' Lily Tomlin, is about to make an appearance on the floor. Give her a big hand!" And then I'd come out from behind the counter and they'd applaud me. I just used to have fun. Whenever I was doing something, I used to make it into theater.

MW: With your career, and life that's moved from the South to the Midwest, to both coasts, you seem so all-American. You are such a strong piece of our culture. Do you have a strong identity as an American?

TOMLIN: I feel like I'm a human being. I don't have any overly nationalistic pride. I want the nation to be what we have believed in the past, when people were really in love with Americans -- especially after World War II. We seemed special. Maybe we weren't, even then, but we thought we were. We thought we were really good people, a good race of humans. I really identify with just humanity in general.

I was lucky enough to have Southern parents and spend every summer in rural Kentucky. I grew up in inner-city Detroit, grew up in a predominantly black neighborhood. At that time in American society there was more ethnicity. There was a bigger mix of humanity. We lived within blocks of people who were fairly well off, professionals. The streets were very wide and the houses were very large, and I went to school with those kids, too. I'd go to their houses and they were larger, better furnished. We didn't even have a car in our family.

MW: All this before Americans were more mobile, better able to segregate themselves socially?

TOMLIN: Exactly. And that's what happened in poor old Detroit. All the "white flight" left the city destitute, no tax base. It was a fantastic city, a great city. And I think it will be again. It's like a template for a city of the future, because it has hit rock bottom so hard. More and more artists are being drawn there because housing is inexpensive. It's just alive, vibrant -- even now. As bad off as it is, there's a vibrant niche culture there that will spread and spread, I hope.

Lily Tomlin

(Photo by Matt Hoyle)

MW: Have you been back recently?

TOMLIN: I played in one of the suburbs there maybe two months ago. My cousin and her family live there, in one of the suburbs. And I have all my old girlfriends from high school there -- not in the inner city, because it's really destitute. I went to high school with Henry Ford II's widow and third wife [Kathleen DuRoss]. I'm going to play Palm Beach soon, so I'll see her when I go down there.

MW: She's a pal?

TOMLIN: Yeah! I got her on the cheer team. That's the kind of place Detroit is. It was rich. It was an industrial city. With unions, it was a very political city, too. Not so white-bread and diluted down. It was zestier.

MW: With the tour, I don't see a particular title. I'm wondering --

TOMLIN: I don't do a tour like that. I never have. People ask me, "When did this tour start?" I say, "Oh, maybe several decades ago on my back porch." I always put on shows. I don't know where I got the notion. I mean, we didn't go to the theater. But I did take ballet and tap and the Department of Parks and Recreation across the street from my old apartment house. It was kind of a tough neighborhood and we had a lot of programs to keep kids off the street. I pitched for a police athletic baseball team. All these different community groups were involved. And I took ballet and tap, as I said. In the summer, we played all kinds of sports. I was a jacks champion. When I was about 9, I played in the junior division.

MW: Junior division of jacks?

TOMLIN: Yeah.

MW: Sounds like you were involved in everything.

TOMLIN: I was! And in the old apartment house, there were so many different kinds of people. The older people there were professionals, but they were on limited incomes so they couldn't move. They wanted to! All these blue-collar Southerners came up to work, like my mother and dad, so my dad could work in the factory. We had 40 apartments in our building, with a common backyard. It burned down in the '67 riots. You think your backyard's so big, but it's like a postage stamp. But all the kids played in that backyard. People hung their wash on clotheslines. [Laughs.] It was a real community.

MW: Were you precocious?

TOMLIN: You could say precocious in some areas, maybe. [Laughs.] People used to let me babysit their kids when I was 10.

MW: Were you sort of the leader of the local kids?

TOMLIN: I don't know. I took a leader role at some points. I was always producing shows! I wanted to do a show so bad and I would try to get the other kids to be in it, and they wouldn't rehearse or show up. They just didn't have the interest in it, and I did. I did magic tricks. I used to say I was the world's first performance artist. I'd tap dance, I'd do ballet, I'd tell jokes I'd seen on television. I could cut a rope and restore it. I could float a ball under a silk. [Laughs.] What I -- Do you really want to hear this?

MW: Yes!

TOMLIN: When I was pretty young, maybe 8, I'd come home from school and read a Red Ryder comic book. In the back they had all these joke items, like hand buzzers and dribble glasses. All this bad joke stuff. Plastic vomit. Ice cubes with flies in them. Anyway, it was, "C.O.D., send no money." I'm thinking I'm the only kid hip enough to get this, so I'm going to get all these items for nothing. [Laughs.] I sent for all this stuff. I came home from school one day and my mother meets me at the door and says, "I want to know if you ordered a bunch of old junk from a comic book." Oh, I was just elated and wanted to get my hands on it. She said, "You can have it when you pay me back." I said, "How is a kid supposed to get any money?"

"You could do things for the neighbors."

It was epiphanous. I told my mother later it was the most important thing she ever told me. I started a dime business. In those 40 apartments, I'd take out your garbage for a dime. I'd go to the store for a dime. I'd walk your dog for a dime. I had drawers full of dimes. Then I would take the money downtown to Abbott's Magic Shop and I would learn a magic trick. I was mad for magic. But not sleight of hand. I was totally lazy, so I would buy apparatus. [Laughs.] I didn't stay with it, but I was so fascinated by illusion.

MW: This apartment house was an amazing world for a kid.

TOMLIN: And there was a botanist who lived in the building, one of the retirees who couldn't move. Mrs. Rupert. Mrs. Rupert had decided I was the kid in the building who had the most potential to "rise above my station." Those are her words.

MW: Mrs. Rupert was right, I suppose.

TOMLIN: I was 8, and she got my mother to let me come over every night after supper. Her husband would be out, worked at the railroad. She was terribly, terribly interesting. She was a short woman, very zaftig, and here I was so lanky, but as tall as she was. So she was like a girlfriend almost, like another kid or something.

Lily Tomlin

(Photo by B Patterson)

MW: Have you written many of these memories?

TOMLIN: No, no, I haven't.

MW: Aren't you tempted?

TOMLIN: Sometimes. My partner Jane and I, we sometimes use our backgrounds a little bit in pieces, but really not identifiably. I might reference my neighborhood or something. But, yes, since you said that, you encourage me to do it. I would think, well, everybody's got these stories. They're just time and place, and the players change a little bit.

MW: It's true that everyone has these stories, but so few seem to remember them so expertly.

TOMLIN: I remember this stuff, but not my address. And Mrs. Rupert was such a big part of my life. I'd go by every night and walk her Chihuahuas and I'd get a dime. We would read The New York Times and I had to write down words I didn't understand and look them up.

MW: She was your Auntie Mame.

TOMLIN: Yeah, she was like my Auntie Mame, in a sense. After that, we'd have a little tea and petits fours. [Laughs.]

She was very conservative. She hated Adlai Stevenson. Hated him. She was so pixilated. She told me she had helped capture and indict Alger Hiss when she'd been a phone operator, before she became a botanist.

Every Saturday she would take me downtown to Hudson's, which was the big department store in Detroit, which has been torn down, sadly. She was trying to educate me to marry well and run a big house. To be extremely well off and have a staff. She taught me how to buy linens and tone your wardrobe with your stockings. I thought it was all hilarious. I'd have to wear gloves and a hat and carry a purse. I had to be able to open the purse and retrieve anything I wanted without looking. A lady is capable of this.

So, in the winter, your nose starts to run when you go from the cold outside into a warm tearoom. Hudson's had everything -- a post office, a tearoom.... So, if we were going to stop in for me to get a hot chocolate, we'd duck up a side street and go into a doorway and blow our noses. Mrs. Rupert thought she was very elite. [Laughs.] Blowing our noses. And here we are, both of us in hats, and we'd go into a tearoom. Sure enough, you'd see some poor woman who had not blown her nose. Her nose is running and she's trying to get napkins out of the napkin holder. And Mrs. Rupert would, like, give me the elbow and nod toward that woman. [Laughs.]

MW: Mrs. Rupert is reminding me of a character I just saw you play in a short, The Procession.

TOMLIN: Really? But she's so, you know, bourgeois. Mrs. Rupert thought she was quite superior to everybody else in the building. She wore a hat and fox furs to the garbage can.

Finally what happened, when I was about 12 -- I'd had a long history with Mrs. Rupert by now -- I was doing my shows. I never told her anything about it. One day she tells me that Mr. Rupert is going to be off the next evening and he'd be home. I said, "I'll come over tomorrow and do my magic show for you." And she hit the ceiling. "Don't tell me you've been wasting your money on magic tricks!" I was so insulted. I was really pleased with my act. She said, "Don't you know that's illusion? If you're not careful, you're going to end up in show business." [Laughs.] I was just furious. I stopped going to see her.

Then she tried to entice me and my brother -- he was about 8 -- over to her apartment one evening. She opens the window onto the backyard and invites me over. She says she wants to show us something very special. So my brother and I are thinking we're going to see a dead baby or something. [Laughs.] We go in and she gets [whispering] very quiet. She makes sure all the blinds are down and she brings out a big box -- a wooden, ornate box -- and puts it on the table. She opens that box, and there's another box inside. She takes that box out and opens yet another box. There are three boxes. Then she pulls out this long thing wrapped in a chamois. She unwraps it and says, "This is the knife that killed Mussolini."

MW: What?

TOMLIN: That's what she told us! [Laughs.] And we didn't really know who Mussolini was or whether he'd been killed with a knife or not. We were so disappointed.

MW: That memory must've been going through your head while you were shooting Tea with Mussolini.

TOMLIN: [Laughs.] Yes! Mrs. Rupert might've liked that because Maggie Smith was in it.

MW: The richness of your childhood seems not to have been wasted at all.

TOMLIN: Growing up the way I did, I saw so many different kinds of people. It never occurred to me that I wasn't like all of them, whether I thought they were great or not. I saw everybody as awful, as cruel, as wonderful, as kind, loving, depressed -- all over the map. Different groups of people, different ethnicities, everything. They weren't so different. They seemed different, but they weren't so different. It was really important. It really did make me have an affection and empathy, really, for most all people.

MW: Beyond people, you've also got an affection for elephants?

TOMLIN: I've been advocating for elephants in captivity for a while. And lots of other things. It just happened that that I became kind of focused on that here in L.A. because we had elephants at the L.A. Zoo that were in meager circumstances. Then I began to read about elephants, and people began to tap me for other cities like Seattle and Dallas. I've gone there and I've advocated.

I was friendly with Sheila Nevins at HBO, so I pitched the idea about doing some kind of documentary about elephants in captivity. We managed to do that last year. But there were many people involved. The young woman, Amy Schatz, who was the HBO director/producer, she won a [Directors Guild of America Award] for directing [An Apology to Elephants], and I won an Emmy for narration.

MW: What other efforts have gotten your attention?

TOMLIN: I've always been active in women's rights, the women's movement, gay rights, fundraisers for female politicians.

MW: I think I spotted a Hillary Clinton tweet from you not long ago. Are you part of the Clinton 2016 push?

TOMLIN: Not officially or anything. I so much don't want a right-wing person to be in the presidency. I'm so afraid everything's going to go on this next election, that there's going to be more seats lost. If the conservatives control the Senate and the House, I dread to think what will happen. It won't matter who's the president. It's bad enough with the obstructionist stuff that's going on all these years with Obama. I think many advances could even be repealed overnight.

Lily Tomlin as Tommy Velour

MW: Has your political involvement increased over the years?

TOMLIN: As I said earlier, Detroit was always a political city, a lot of unions. We were conscious of it. My dad was in the union. My dad was a Southern guy, basically a rural kid who grew up with 10 brothers and sisters. A tenant farmer. Really, my dad only went to the third grade. But he was innately intelligent. He would've been a toolmaker, but he really couldn't write to any real extent. But he could read a blueprint and put a machine together. He would come home with these little things that he'd produced and I knew how proud he was that he was able to do that, that the toolmaker would go to him and be able to say, "I need this part. Can you put a machine together?" And he'd say to me, "Babe, this is what the old man did today." [Laughs.] So I knew how much it meant to him. I saw the pride he had in that. So, politically, you just understand about people. You don't intellectualize it. As a kid, you know what it is to have money or not to have money. People scraping by, getting laid-off, not having a job for five or six months.

I remember when my dad was laid off and rebuilt a lot of the porches in our old apartment house. I was really a little kid, but I can remember hanging out on a porch all day while he rebuilt a new porch and banister and steps. I was just so proud of that, that he could build those porches.

MW: Did you and your wife consider having kids?

TOMLIN: Of course we talked about it. But I don't call Jane "my wife" at all. That's a heterosexual stricture. When people used to ask, "Are you and Jane going to get married?" even before it was possible, when everyone was fighting for it, I would say, "Well, I was hoping the gay community could come up with something better than marriage." Jane would say, "You've got to stop being so flippant about it, because the issue of marriage is really serious and important to a lot of people." And I knew that. Especially for friends, same-sex couples, with children. They ran and got married right away.

I lightened up about it, and I do realize it's meaningful. It's meaningful for it to be acknowledged in the culture. I'm astonished at how far the gay movement has come in 20 years. It's staggering.

MW: As culture and politics go, I'm guessing plenty of Washingtonians loved you on The West Wing.

TOMLIN: I loved that, too. When it came on the air, I thought, "How has it happened that I'm not in this?" I had my agent reach out to Tommy Schlamme, and Aaron Sorkin at that time. And then Mrs. Landingham was killed in that episode -- no doing of mine whatsoever, believe me. She was so loved. But they planned to use Mrs. Landingham kind of as a Jiminy Cricket, but it didn't really work for them. Kathryn Joosten became a good friend of mine. I knew her from Murphy Brown, and then later I did a stint with her on Desperate Housewives. I played her sister. We were good friends.

MW: I would think, particularly as a team with Jane Wagner, you'd have enough clout to do any project you like.

TOMLIN: Well, not quite, Will. [Laughs.] Yes, it helps, of course. But not everybody maybe feels the same about me. It happened that Aaron Sorkin liked me and was probably pleased that I wanted to be on the show.

And I am allowed to tell you -- although I usually hold back because I don't like to tell too much about upcoming projects -- that Jane Fonda and I are going to do a project for Netflix. A series.

MW: Netflix is on fire right now.

TOMLIN: And they're just great people, so easy to be with. Marta Kauffman, who was one of the creators of Friends, she's written the first episode.

MW: It's not a 9 to 5 reunion, is it?

TOMLIN: Aw, no. That would've been good. Maybe we can get Dolly in some part. That would be fun!

MW: I know I've got to let you go, but before I do I want to make sure you know there's at least one group of gay fellahs quoting your 9 to 5 Violet Newstead character routinely.

TOMLIN: [Laughs.] "I know just where to stick it."

Lily Tomlin performs Friday, March 28, at 8 p.m. at the Music Center at Strathmore, 5301 Tuckerman Lane, North Bethesda. For tickets, $27 to $81, call 301-581-5100 or visit strathmore.org.

...more