''We are an ahistorical people,'' Cleveland attorney Leslye Huff says. ''The number of lesbians in this town, who are under 40, who don't know that we had a monthly newsletter called What She Wants, that was run purely on volunteer energy and was just as present in our community as the Gay People's Chronicle,'' she says about the LGBT newspaper still published in the city. ''It's that kind of thing.

''We don't have our history, so we don't connect the dots in the same way.''

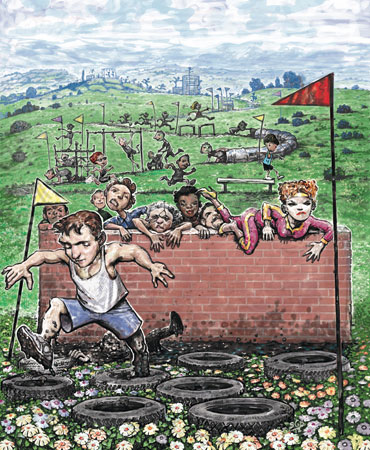

(Photo by Illustration by Scott Brooks)

Huff, who recently worked with the city of East Cleveland, Ohio, to pass an extensive nondiscrimination policy that provides LGBT people with the right to bring a civil lawsuit if the city fails to enforce the law, has a long history of combating racial, sexist and LGBT intolerance — and notices when people lose track of that history.

Connecting the dots is difficult within the LGBT community, but not the least of all because — as Huff and others say — the LGBT movement is not an organic movement. Although there are extensive similar problems faced by lesbians, gay men, bisexual people and transgender people, the difficulty of connecting the dots only becomes more difficult once it becomes clear that not everyone is attempting to create the same drawing.

From defining equality and looking at who's left out, to considering electoral politics, strong advocates of LGBT equality across the country are picturing, thinking about and working from very different ideas of what the LGBT movement is aimed at accomplishing.

Talking with one of the first out lesbian law professors, Rhonda Rivera, and the first out Episcopal bishop, Gene Robinson, one gets a glimpse into that history Huff values. Hearing from a 17-year-old high-school senior in Idaho, Marisol Cervantes, and the director of a program that works with homeless LGBT youth, Mark Erwin, adds further insights, as do the voices of trans activist and law professor Dean Spade and undocumented activist and law student Prerna Lal. Rory O'Malley performs on Broadway but is working for marriage equality with Broadway Impact, and Mimi Planas helps the Log Cabin Republicans in Miami open up the pathway for more conservative voices for equality. Finally, as his time at the helm of the Human Rights Campaign comes to an end, Joe Solmonese shares his thoughts on what has been accomplished — and why.

From Seattle to Miami, from Boise, Idaho, to New York City, these activists and advocates of all stripes believe that much is happening. Some like Spade, though, don't necessarily see what's happening as all good — and see a dramatically different direction that would be best for the pursuit of social justice.

WHAT IS EQUALITY?

Joe Solmonese

Retired law professor Rhonda Rivera joined The Ohio State University College of Law faculty in the late 1970s. She joined Douglas Whaley, a prominent contracts professor who today is openly gay, on the faculty.

Looking back, she says that the attitude at the time was not much different from the way a church group might treat a gay organist: ''Many people in the school thought, 'These are our queers. Doug and Rhonda are our queers, and our queers are different. As long as there's not too many of them.'''

And, though she says she didn't focus much on it at the time, the overt and subtle discrimination was difficult — from tenure questions to bathroom-stall scrawls.

''When I left OSU and I walked out of there for the last time, it was the most relieving and exciting thing. I never realized how oppressed I felt in that building. You maintain a certain facade.''

Looking to today and the changes made since, she says, ''There are lots of gay people in lots of important places now. One of the things we learned about being women in the law was when there was only one or two women in the law school, they were treated not well. But as soon as you got enough women that they could stand with each other, five or six, maybe 10, then they were afraid to treat you badly. So, we used to talk about getting a critical mass of women in a law school. Until you achieve the critical mass, you can be shit upon regularly. And, once you got the critical mass, maybe people still didn't want you there, maybe they didn't like you, but they were afraid to do anything about it.''

Applying those lessons to Congress, she says, ''When you look at the people like [out gay Rep.] Barney Frank (D-Mass.), [out lesbian Rep.] Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisc.), I'm sure these people went through very, very lonely times. Barney Frank, being the only open person in the 535 people in Congress, I'm sure that he has kept up a facade and that he has battle wounds all over him — of just taking it. He knows what people called him, he knows how people treated him.''

When HRC's Joe Solmonese leaves the nation's largest LGBT political organization in June, he will have been there for more than seven years. Looking at the changes over the course of the LGBT movement's past 20 years, he says, ''The thing we don't appreciate enough is the organizing mechanism that, in many ways, has empowered people to be out and open about who they are.''

Specifying, he says, ''We went into the American workplace and said, 'Until we can change the laws so that LGBT people can be married and have federal workplace protections, we'd like to engage you in a business-based conversation about creating a safe and welcoming and equitable experience for LGBT people.'''

He's upbeat: ''I think it's the great story of our movement that we did that. Support for marriage equality going from 33 percent to 53 percent. Who are those people, those 20 percent? They're those people in those settings, who work side by side with LGBT people whose views are changed because they have now been in the company of an LGBT person.''

But, as Solmonese knows all too well, the success to which he points also is the success that has bred frustration in younger activists who are demanding equality from the White House fence — to Broadway, where Rory O'Malley performs in Book of Mormon. In his off time, though, O'Malley was a co-founder of Broadway Impact, a group that formed to push its support among Broadway performers and others for marriage equality and other LGBT issues.

''I want all of this tomorrow, I'm in that camp. I don't think we should be waiting for President Obama to evolve. I think it should happen now,'' O'Malley says in between shows at a coffee shop in New York City. ''But, at the same time, you have to be excited about what has happened — and be empowered by it. I think we need to be empowered that so much has happened in such a short period of time — and much more remains to be done.''

WHO IS LEFT OUT?

Prerna Lal

''I think everyone has a different concept of movement,'' Prerna Lal says. ''I think for some it may relate to a list of issues that are pertaining to, say, the mainstream LGBT movement. I'm not sure if that list is what I share in common or not. For me, winning the movement means also winning rights for everyone, and that includes health care for everyone and immigration rights for everyone who's not seen as American or not seen as 'part of.' I think we have a long way to go.''

Lal, who describes herself as ''a queer Fiji-Indian (Pacific Islander of South Asian descent), currently a law student at The George Washington University,'' serves on the board of Immigration Equality and is an intern at the National Center for Transgender Equality. She also is ''out'' about her status as an undocumented immigrant, which she says was ''scary at first'' — but, she adds, ''There's a growing acceptance of me being out there.''

It also gives her insights, in small ways and big, about how being the ''other,'' even within the LGBT community, can be a problem.

''If you're dressed in a traditional Indian [dress] at a gay bar, and you're told, 'Sorry, it's Ladies Night,' by the bouncer there who assumes that because you're in ethnic wear, you're not gay or lesbian or bisexual or transgender,'' she says, ''that's an issue that has to do with our perception of 'gayness,' and how it's so white, I think, generally. It bothers me, because I live that life.''

Huff acknowledges those issues, but puts them and similar issues — for all oppressed groups — in the context of her early life.

''My first memory of the larger world was of the picture of Emmett Till's face on Jet magazine,'' she says of the 14-year-old Chicago teenager who was brutally murdered after some claimed he had flirted with a married white woman while visiting family in Mississippi. The July 23, 1964, issue of Jet contained graphic pictures of Till's body after it had been pulled out of the Tallahatchie River.

''I felt the energy of my entire little town, all of the adults in my town, whether it was at church or at school or on my street, that's all that people talked about. It was as if they wanted to be able to say they could keep their children safe from that ever happening again. But they couldn't. They couldn't make the promise. So, there was this almost tacit agreement that if they couldn't promise the children it would never happen again, they would just promise to worry about it happening,'' she says.

''So that is what informed my early life — and the countermanding stories from my own personal family that were essentially tales of how we transcended all that. Those two things happening simultaneously in my head created an activism in me: The ideal was possible, and if we just worked hard enough and did enough and sacrificed enough, things would change.''

That has been the work of Huff's life. Today, talking about her work on racial issues, on women's issues and on LGBT issues, she says, ''It's all one thing for me. Whenever I'm sitting in one particular group, I'm always thinking about the group that's been left out of that group. That's just the part of what's going on in the back of my head as I speak.''

But, she says, not everyone has always done so. Talking about the late-1980s, she says the groups that now make up the ''LGBT movement'' were still very segmented.

''There were gay men over here, bisexuals and transgender people virtually didn't exist … in the scheme of things, and then there were lesbians,'' she says. Then, somewhat a function of the AIDS crisis she says, ''What happened is, we looked around, and the lesbian organizations dissolved, and we were left with this scenario of 'LGBT.'

''But none of the work had been done, really, to address the misogyny among men, or the racism among whites, or the tendency to cluster and be almost ghetto-like among minorities, or the tendency to let white people lead whenever there was a choice, or the invisibility of bisexuals. None of that work had been done. But there we were, talking 'LGBT.'''

Gene Robinson

Bishop Gene Robinson adds that, within the LGBT community, work also is needed to address religious issues.

''It's really interesting having a foot in both communities — the religious community and the LGBT community. The fact of the matter is, 95 percent — and that's my figure, not based on anything but me and my own perceptions — 95 percent of the discrimination that we experience is the result of religion. Even nonreligious people use what they have soaked up in the culture of these religious views,'' he says.

As with education and work being done on race issues and sexism, Robinson says that, within the religious communities, change is happening. ''I often say the church that you left may not be the church that's there now. If you're out of a denomination that is just hopelessly backwards on this issue, there are other places. There are places where you'll be welcome and where you can be who you are and be affirmed.''

For some, though, the work to be done is far more fundamental than just a matter of education or being more inclusive of the ''others.''

''I should be straightforward that I don't usually use the term 'LGBT equality' because that term has come to really centrally indicate legal equality as a focus and goal of a certain strain of LGBT activism,'' Seattle University law professor Dean Spade, a trans activist, says. ''And a lot of my work is about critiquing the centering of just trying to get antidiscrimination laws, hate-crimes laws, marriage and military inclusion.''

He looks at the path forward very differently from, for example, HRC's Solmonese.

Dean Spade

''My work has been focused on centering racial and economic justice, and asking less what the law says about lesbian and gay and bi and trans people and more how legal systems are impacting us and how we can confront that,'' Spade says. ''So, a lot of my work has been about shifting the focus from marriage, military, hate crimes, antidiscrimination laws to looking at how criminal systems, immigration systems, social service and social welfare systems impact queer and trans people who are highly vulnerable to different forms of violence, poverty, homelessness, immigration enforcement and criminalization.''

Robinson, perhaps unsurprisingly, echoes a similar social justice frame in talking about his work with the church and throughout the country. In his work with St. Thomas's Parish Episcopal Church in D.C., he and the church plan to begin a ''center for nonviolent conversation,'' aimed at ''changing the nature and tone of the debate in Washington'' — ''not just tolerant, but respectful, and profoundly serious about loving your neighbor as yourself.''

Robinson, like Spade, is not averse to calling out the shortcomings of those involved in advancing LGBT equality, and he squarely puts forward his views on the failure of the gay and lesbian world to engage fully on gender-identity issues.

''I also think the gay and lesbian community has a huge learning curve ahead for it,'' Robinson says. ''In my experience, though we let the 'LGBT' roll of our tongues pretty easily, for the most part the gay and lesbian community is really ignorant about this incredible diversity of conditions that exist under the umbrella called transgender. What the transgender issue does is to say: This is way more fluid than anyone has thought before.''

Of LGBT organizations' efforts to advance trans issues, he says bluntly, ''It's like learning to not sound racist without changing your views. I think we have gotten a lot smarter about our language and so on to include trans people, but I don't see a lot of hard work going on that is beyond lip service.''

Lal agrees — and points outside the LGBT community as well.

''We're definitely more behind on the trans issues in society than we are on the LGB issues,'' she says. ''We still don't see gender as something that's a continuum, or we don't see it as something that's not fixed. It may have to do with our acceptance of women in general or femininity. We disparage women, we disparage trans people in some of the same ways because we are disparaging someone's right to be masculine or feminine.

''We're at a place when I think we can focus our efforts more on 'T' issues, which I'm trying to do personally myself.''

At the Ruth Ellis Center, Detroit's program for LGBTQ homeless youth, program director Mark Erwin points to national attention on marriage equality as ''incredibly important,'' but says that ''there are other things, too, that we need to recognize as happening on a national level.''

Of the population that he works with, he notes, ''We know, of the 1.7 million homeless and runaway youth in the United States, up to 40 percent identify as LGBTQ. That is a hugely disproportionate number.''

States away, 17-year-old Marisol Cervantes is still in high school, but is likewise working on youth issues.

''I started coming to the planning meetings,'' she says of the youth nights held by the Idaho Safe Schools Coalition that began her involvement in LGBT issues. ''I started volunteering all the time, and then eventually I started writing workshops and going to conferences and presenting the workshops I wrote. Now, I'm investing my time and energy in creating new leaders for the organization.''

Mark Erwin

Erwin celebrates that impact — the differences that he says can happen to advance equality once LGBTQ youth have an affirming environment.

''When you have an environment, really great things can happen for young people,'' he says. ''And we see that all the time at the Ruth Ellis Center. People tell us, 'We can't believe the impact that your young people have.' They literally wrote the anti-bullying policy for the Detroit Public School System. And we get questions: 'How are homeless youth able to write this policy?' And our answer is: 'Because they're the ones directly affected by it.'''

O'Malley, the Broadway Impact co-founder, is strident in his activism — but sees a distinction between work for marriage equality or trans issues or LGBTQ homelessness and partisan political issues.

''There's a difference between knocking on doors for Barack Obama and getting arrested for the people of Sudan,'' referencing George Clooney, who participated in both a protest against Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir that led to Clooney's arrest and the Los Angeles premiere of 8, Dustin Lance Black's play about the Proposition 8 trial. ''If you keep the candidates out of it, I don't think that people have a problem with it. Obviously, I have my own political views, in terms of candidates that I would support, but I think there's a way to separate that. And I think it's important to separate it because it is — it should be — a bipartisan issue because this is civil rights.''

WHAT ABOUT POLITICS?

Rory O'Malley

And yet, the attention in 2012, inevitably, turns to partisan politics.

HRC's Solmonese, who serves as a co-chair of President Obama's re-election campaign, says, ''I think we're in a place that none of us imagined that we would be a decade ago, but I think we're at a significant crossroads now. I think we have the potential to continue on this trajectory or to come to a grinding halt — depending on what happens in November.

''I hope that Barack Obama gets re-elected, but I think it's going to be more difficult than people think.''

O'Malley sees the tension between pushing Obama to do more and pushing for his re-election, a constant issue throughout Obama's presidency, as a good thing — and necessary: ''With Obama, it is a healthy thing that the gay community has been dissatisfied with him for his three years — even though he's the most pro-LGBT president we've ever had. However, it is absolutely vital that no one is satisfied, and I am very proud that we have a community that is not satisfied with just what we're getting. We need to fight for every single inch of it.''

Gay Republicans are familiar with needing to fight for every single inch, both within the LGBT world and the GOP world.

''If you're visibly gay among the Republicans and visibly Republican among the gays, you start to change minds,'' Miami Log Cabin Republican co-chair Mimi Planas says from Florida. ''What we've also been able to accomplish is go ahead and bring out the LGBT community that do have Republican principles but were afraid to show them out of fear of being judged among the Democrats. Because, if you're gay, you better be Democrat. That's the myth.''

But for others, like her, who she says care more about economic issues or foreign policy, Log Cabin Republicans are there. ''They just don't believe in the Democratic party.'' And now, with HRC's early endorsement of Obama — which came in 2010 before a single Republican primary — Planas is incredulous.

''There are many groups out there that claim to be nonpartisan in the LGBT community, but they're not,'' she says. ''When I heard that HRC declared their support for President Obama without us even having the first debate in the primary, it was very disappointing because they didn't even care to try to fool us anymore. They just blatantly said, 'Fuck it, we're going to support the Democratic candidate. Period.' Because they're one-issue organizations. What about the rest of everybody else's lives? You have gays and lesbians that own their own business, you have gays and lesbians that serve in the military, you have gays and lesbians the current economy is impacting right now. And what they don't understand is that gays and lesbians care about that, too.''

But it's not just the Republicans criticizing this approach. Spade, the law professor and trans activist, makes a similar criticism from the opposite direction. ''That's what's wrong with a political strategy that centers legislative wins, wins in courtrooms and wins in the corporate media, because there's only certain kinds of people who can be portrayed as 'deserving' justice in those frames,'' he says. ''And so you end up creating a very narrow set of demands that only will provide relief, if to anybody, to the people who are not the least vulnerable.

''And, I think even more than that, most of the wins are just pure window dressing.''

A DIFFERENT WAY?

Leslye Huff

As the media focused early this week on Vice President Joseph Biden's comments about marriage equality, and attention turned to Obama's own now-''evolved'' position on the question and the marriage amendment vote in North Carolina, it again became clear how quickly marriage equality can suck up all the oxygen in the room.

Rivera, the retired professor, says, ''I'm surprised that so many people think marriage is so important. I would have thought – and I still do think – that [the Employment Non-Discrimination Act] would be, in my estimation, a lot more important than almost anything I can think of.

''Being a lawyer, I want people to be able have jobs without getting fired because they're queer. And so the fact that ENDA hasn't passed, and yet, here we are, we already have states having marriage, I think is very surprising,'' she says. ''Evan Wolfson, from Lambda [Legal], really was the first person that I knew who pushed for marriage. I can remember him talking and thinking, 'Oh yeah, that'll be the day.'''

But, as Rivera says, ''Here we are.''

Lal questions the priority that marriage has been given as well.

''I support marriage equality. I think you should have the right to arrange your family relations however you want to arrange them. But I also think focusing on it so much does [push] us away from other options,'' she says over coffee in D.C. ''I think marriage — maybe it's my age, but I don't think it affects me in the same manner as other things, like housing, health care, employment discrimination would affect me. That's why I'm a little — 'upset' is probably not the right word — disappointed, I think, by the focus on it.''

It is not only marriage that is front and center in critiques of the modern LGBT movement. There also is the question of race.

Huff questions whether the theme, oft repeated, that the black community has a problem with gay people, is at all fair. Looking at history, she points to support at LGBT marches in D.C. in the late '80s and early '90s, saying that the diversity on the stage was constant and that black leaders, from Jesse Jackson to District officials, were present to support the march. Today, even, she notes, ''You can't find another cluster in Congress that's more supportive of LGBT rights than the Congressional Black Caucus. The progressives, yeah, but many of the black folks belong to that.''

Of the questions about how to move forward to address the perception that blacks and gays don't get along, Huff posits a theory of why it hasn't changed.

''This is my theory, and I'm old, so I can have all the theories I want. I think it allows black people the excuse of staying in the closet … and it allows white people to keep the status quo of leading the pack and making all the decisions. It leaves us in that same spinning circle, not addressing racism, not addressing the leadership issues, and it gives both sides tacit approval to do that.''

For Spade, change must go much further to make a real impact on the most vulnerable people.

''When I look at the history of the United States and I look more broadly around the world, significant social change that really gets at the root causes of harms and maldistributions occurs when the strategy is mass-mobilization and when huge numbers of people who are affected by something are standing up against it and will not stop until it changes. And it becomes impossible for the condition to be the same,'' he says. ''Significant social change does not happen through asking elites to change things. That hasn't tended to work out for the people who are the most vulnerable.''

As an example, he takes aim at an early accomplishment for LGBT rights claimed by the Obama administration and people like HRC's Solmonese.

''The obvious example that has been heavily critiqued in queer and trans communities is the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd [Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention] Act. A lot of people-of-color-centered queer and trans organizations stood up and said, 'We don't want this. This actually does nothing for our communities. This does nothing to prevent our deaths. It just adds more resources to law enforcement, which is one of the main perpetrators if not the central perpetrator of violence against our communities,'' he explains. ''If we wanted to prevent the death of trans women who are being killed every month around the U.S., we would make sure they had housing or we would make sure they had a safe way to work or we would decriminalize prostitution so it wouldn't be as dangerous for them to do that work if that's what they're doing.''

HOW DOES IT END?

Marisol Cervantes

In finding those frames, making those adjustments and reaching those goals, the question at some point turns to a look past the struggle. Gene Robinson, hopeful about the future, asks a question that came up a few times in discussions about the LGBT movement: ''Will we still be a tribe after equality?''

He answers his own question: ''I would like to think yes, but I think that's still to be determined. I think it will matter about how we see ourselves. The greatest gift that comes from being gay, for me, is that it gives me the tiniest window into what it's like to be black or in a wheelchair or to be a woman and so on. Because, other than that one trait about me, I fall into the oppressor status on all of the other 'isms.' So, how will it effect the gay community if we're no longer discriminated against?''

Rivera echoes Robinson, talking about her conversion to Judaism as an adult.

''Being a Jew is being in a community. There are people who are just like you, who have certain holidays and things the same. One could argue that Judaism without community is not Judaism. Well, the gay and lesbian community has a distinction, and we have part of it because we are, quote, oppressed,'' she says. ''Will it be that when we're, quote, no longer legally oppressed, that we really have no community? I think that would be sad — and I think the country would be less because of it.''

Robinson goes further down that path: ''I would like to see a world in which people of color understood their connection to women and women understood their connection to LGBT people, and so on. If we can see our own liberation connected to the liberation of everyone,'' he says of LGBT people, ''then we will have really done something.''

Cervantes has both optimism and hope at 17 and deep in the heart of what politicians like to call ''real'' America.

''I think Idaho has found a resource, and that resource is the coming generation,'' she says with a smile on her face. ''Take 10 years, we'll have activists all over the place. It's a force to be reckoned with. … [R]egardless of who wants it or not, change is going to happen. It's going to be huge.''

Planas, the Log Cabin co-chair, sees her circumstances as remarkably similar: ''I know I'm going against the grain, and I know that it's difficult what we're doing. I'm no fool. But to see the look in people's eyes when they're relieved that they're not the only ones who really don't want to be Democrats because they're gay – that is a big deal for me. Awareness is educating.''

Critics from the left see progress, too.

''We've come a long way in 10 years,'' Lal says, pointing to her own experience. ''Visibility … has led to this idea that the time has come. And that's really helping the legal victories along. If you read, 20 years ago, Bowers v. Hardwick [the 1986 Supreme Court case upholding sodomy laws as constitutional], you're like, 'Really? Are you really trying to say that?' And, today, it's not acceptable.''

For Spade, even as he criticizes groups like HRC and other mainstream LGBT organizations as focused on ''a white-centered, upper-middle-class-centered gay and lesbian rights politics,'' he says, ''[S]ometimes we can find ways to collaborate. … [A] lot of us are consistently trying to collaborate with people there and have deeper relationships with people inside those organizations and respect them as fellow travelers.

''It's not about setting up enemy camps. It's just about really trying to discern and evaluate what works and what doesn't work, and, whenever we can, trying to mobilize the larger gay and lesbian rights organizations to stand up and speak out about things like CeCe [McDonald]'s trial [in which the trans woman was accused of murder after defending herself with a pair of scissors, leading to the death of her presumed attacker] or to use their muscle if they're willing to, which is uneven, on various issues.

''At the same time, having a realistic recognition that the way they're structured, and who they're accountable to in terms of wealthy, white donors and foundations, it's unlikely that they're going to have an about face.''

Solmonese defends the formal, legal equality that he sees coming in the near future as being important and based upon a public education that he sees as having been made in recent decades.

''When we do get about changing the laws in a way that brings us full equality — whether that is in terms of our protection and being free from discrimination or whether that is our families under the guise of marriage equality — when those changes come about, I think we will be a long way towards being finished … because we've laid such an incredibly strong foundation that manifests itself in the public opinion of the American people.''

''Over a five-year period,'' Solmonese says, there will be a series of successes on the legislative and judicial front to ensure marriage equality and employment and housing nondiscrimination. ''I think we're close to that window where all of a sudden things fall into place. And I think we're a lot closer to finished at the end of that period than most of the other movements for social change in this country have been.''

O'Malley looks at the future and imagines what that end would look like.

''I see it as being a quiet thing. There's a Kander and Ebb song called 'A Quiet Thing,' saying that love is quiet,'' he says. ''It's not the big, crazy fireworks; it's a quiet thing when you're really in love with somebody.''

''It's not going to be the parades,'' he says of reaching a point where LGBT people are treated equally. ''There will be a day of that, but real equality is just going to be when we're able to take down the signs and just be who we are and it's not going to be an issue.''

Rivera returns to the importance, in her mind, of community: ''I'm not sure that we'll ever be totally — even in spite of what the law may say — totally, in many people's minds, equal. And I have mixed feelings about that. Maybe it would be good to keep some sense of community.''

Huff sums up the path forward by reference to an African word: Sankofa. ''The image of 'Sankofa' is of a bird flying forward but looking backward,'' she says. ''The idea of 'Sankofa' is that we look back with humility and honesty so that we can go forward with integrity.

''There's something really wonderful about looking back for the sheer intellectual, honest rediscovery of our past so that we can move forward with integrity.''

Moving forward, as these voices show, is more complex in many people's minds than the legal and legislative equality that often attracts newspaper headlines and makes the nightly news.

From making lives safer for young people to increasing the acceptance of LGBT people across the political spectrum, there is much that remains in changing attitudes and actions of non-LGBT people. At the same time, efforts to educate gays and lesbians about transgender issues and to address racial and religious issues within the LGBT community show that internal work remains as well.

It could be that the right questions aren't even being asked – let alone answered – in order to ensure that those most vulnerable people in the LGBT community will be helped by changes being advanced.

Or, it could be that equality is almost here.

...more